Statement of Transparency: This article begins a multi-part series exploring the current landscape of ultramarathon running as a business. Each installment is an opinion piece authored by John Lacroix, owner and race director of HPRS, and does not necessarily represent the views of the wider HPRS community. Data will be included whenever feasible to back up the various thoughts and opinions shared by the author. Additionally, sources will be cited at the end of the article to indicate where data or quotes were sourced from.

Articles a part of this series will include:

- On the Growth of Ultrarunning – Revisiting the Tragedy of the Commons and Race Cannibalization

- Prize Money – The Key to Ultra Growth?

- The Oligarchy – Who Is Really In Control of the Narrative

———-

In the past ten to fifteen years, I’ve authored two articles on the Tragedy of the Commons and its connection to trail and ultramarathon running. The most significant was the one published on trailandultrarunning.com in April 2012. [1] This piece applied the concept of “The Tragedy of the Commons” alongside insights from renowned outdoor advocates Guy and Laura Waterman to highlight our sport’s risks if we fail to consider the extensive consequences of its rapid growth more thoughtfully.

In this article, I want to revisit the Tragedy of the Commons concept, restate the warning I provided in 2012, and investigate where we find ourselves 12 years after the last time I approached this topic.

What Is The Tragedy of The Commons?

The Tragedy of the Commons describes a situation in which individual users, acting independently according to their self-interest, behave contrary to the common good [8] by depleting or spoiling a shared, limited resource. Ecologist Garrett Hardin popularized the term in a 1968 paper.

The “commons” typically refer to resources like fisheries, pastures, forests, and air that are accessible to all members of a community. Tragedies occur when individuals exploit these resources without considering the long-term impact on the whole community, leading to eventual degradation or depletion of the resource. In the context of this article, “commons” refers to our private and public lands and trails, as well as the people who populate our sport as runners and volunteers.

The concept often illustrates the need for cooperative management of shared resources, regulation, or privatization to ensure sustainable use. It highlights the potential for overconsumption and environmental degradation due to unregulated access and the necessity for collective action or governance to address these issues.

“Some scholars have argued that over-exploitation of the common resource is by no means inevitable, since the individuals concerned may be able to achieve mutual restraint by consensus.” [2] I wanted to touch on this quote from Wikipedia’s page on the Tragedy of the Commons as it relates to ultrarunning, specifically the idea of “mutual restraint by consensus.”

There is no actual governing body that oversees the sport of trail and ultrarunning. While organizations like the Road Runners Club of America (RRCA), American Trail Running Association (ATRA), and the International Trail Running Association (ITRA) have published general frameworks that each entity encourages us to follow as an essential practice as race directors, the reality remains that none of these entities are a governing body and thus hold no governance over events and their directors. In other words, the trail and ultramarathon running business is an absolute free-for-all with no published industry standard and no one entity holding anyone accountable for their actions.

Some race directors get along, but a lot of us do not. As the business of ultrarunning has grown over the last two decades, our collective ethical and moral compass has declined. Most race directors see each other as competition as opposed to peers, and we no longer operate as a community of one. There is also no “mutual consensus,” and through this article I will show you how there is no “mutual restraint.” To the point made on Wikipedia, while over-exploitation of the shared resource was by no means inevitable, we have finally reached a point in our sport’s history where we have realized that possibility.

In an April 2012 article I wrote for TrailandUltrarunning.com, I stated, “Ultra/Trail Runners need to be careful, and as a community, we need to begin to consider ways in which we can avoid the Tragedy of the Commons. The trends are out there, it’s going to happen, and in a community where our races take place through delicate lands and often include delicate land owners.. the time is now for us to consider how we plan to give back. Many races force this into our culture by requiring runners to do 8 hours of trail work in order to even run in the race. I’ve heard many an ultra-runner complain about the trail-work requirement at various races around the country. While I understand their point of view, I’d love for them to understand the bigger picture.. that we can’t always take and at some point, you’ve got to give back or the resource will run out.” [1]

The Growth of Ultrarunning

iRunFar.com published an article in May 2024 discussing ultrarunning growth in The United States Through a Geographic Lens. [3] The article by Zander Chase specifically explored “A look at the growth of ultramarathons in the U.S. from 2000 to 2024, including overall growth in events and their locations, and changes in participant travel.” [3]

While indeed interesting, well-researched, and thoughtfully discussed by Zander, I didn’t pay much attention to the participant travel aspect of the article. My primary focus within the article was the discussion of the growth of our sport. “Since 2000, the number of races in our dataset has grown from 233 to 2033, a 772% increase.” [3] That’s a HUGE amount of growth for sure, but it led to a few questions I provided in the post’s comments section.

My comment was: “This is really great… but we’re missing the “let’s get real” part of the article.

• How many races are begging for volunteers? Back in 2000, veterans taught runners the importance of giving back and how it is a vital piece to the sports puzzle; yet today, there’s a lot of begging for volunteers out there. (Or how many races can’t find enough volunteers without the begging?)

• How many races only field 10-30 runners total?

• How many races sell out?

There is more to this data set that can illuminate the struggles we’re experiencing with our growth, and not having it part of the discussion highlights a more significant problem: We’re ignoring “the big picture” associated with our growth.

So, let’s get real. Let’s talk about races begging for volunteers and how many races only have 40 or fewer finishers. Why? Because this is the potential tragedy I sounded about in 2012, exploring these answers will highlight that we’re our worst enemy and the very definition of “Tragedy of the Commons.”

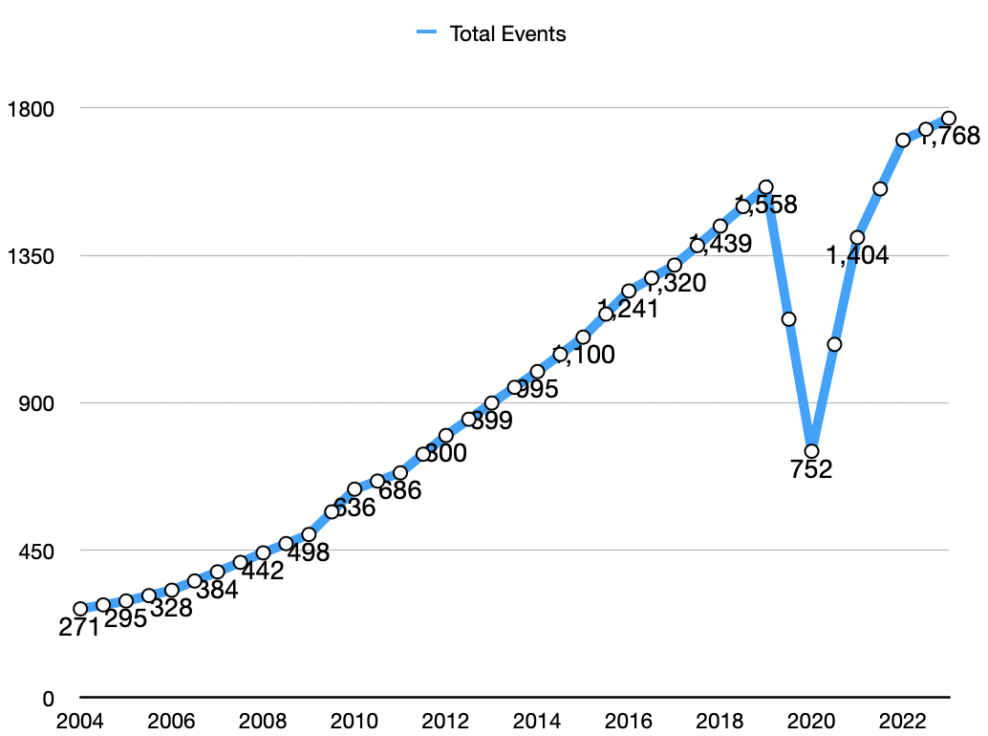

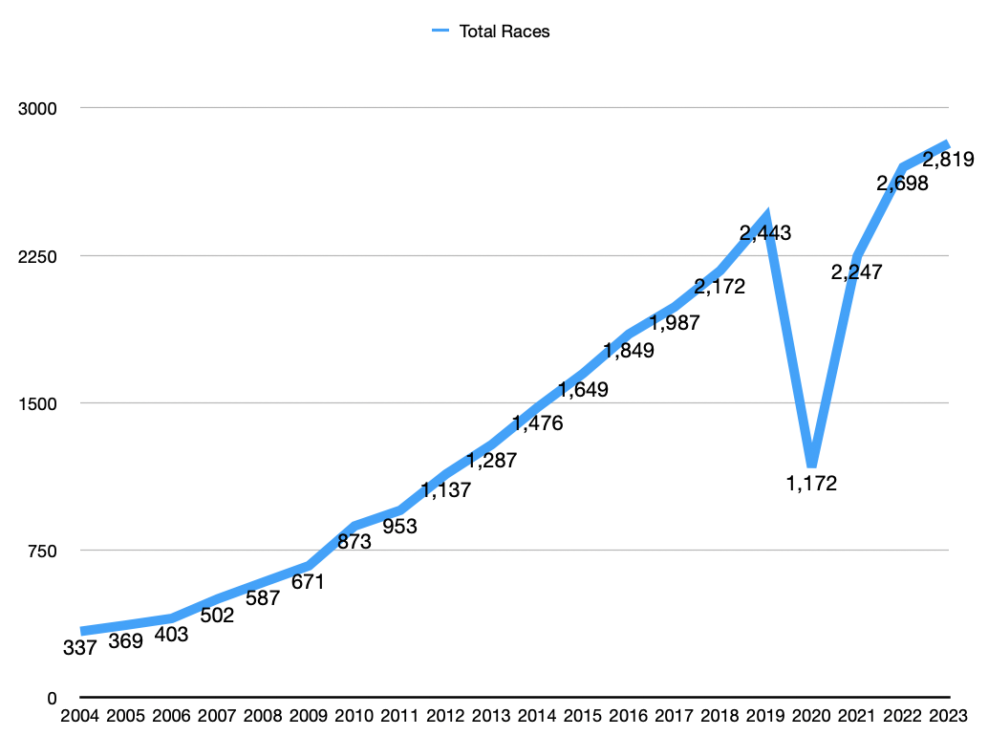

With the utmost respect to Zander’s body of work, I wanted to revisit the data provided by the stats page on Ultrarunning Magazine’s Website. [4] With the data on the site, I tried to create line graphs to visualize a few specific points I intend to make. First, A few notes about the data:

1.) I cannot guarantee the factual accuracy of the data on Ultrarunning Magazine’s website. I believe it is a fact that this data is not entirely accurate, and there may be data omissions. We use UR Mag Stats for reference only.

2.) We’re only looking at data for years 2004 through 2023

3.) Most races only post finisher data and not total registrations or data on total starters. Not all races publish DNF or DNS data.

The data we are specifically looking at is:

• Total Events

• Total Races

• Total Unique Finishers

• Avg Number of Finishers Per Race

Here is what I see within the data that is most glaring…

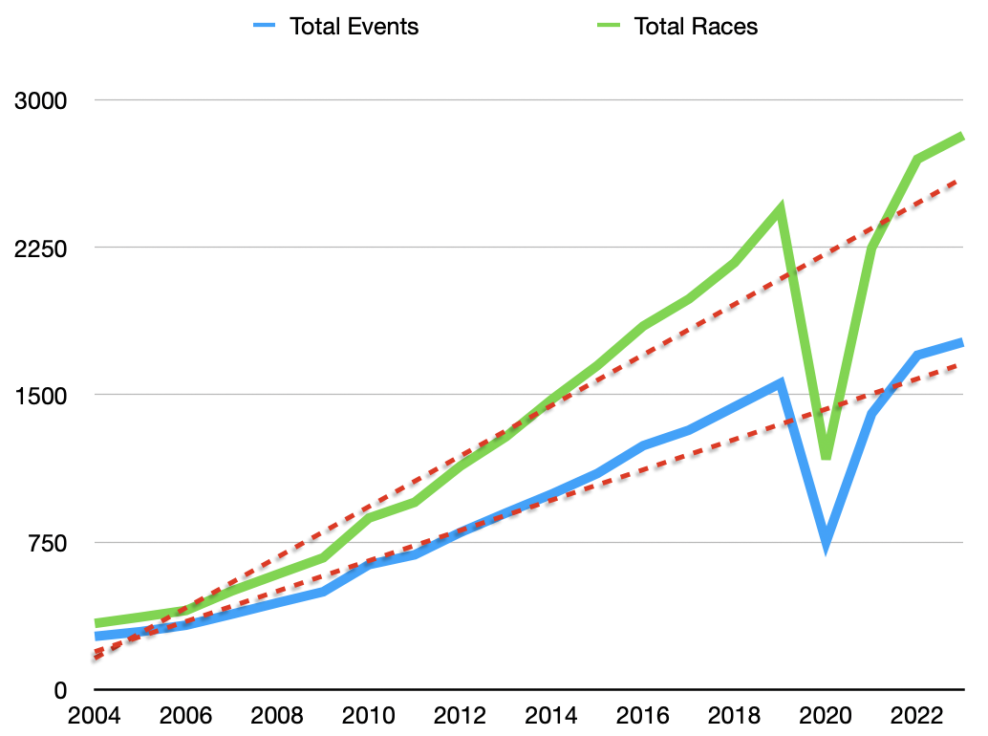

‘Event’ refers to the number of events with an ultra-distance present. ‘Races’ refers to the number of ultra-distance races in those events. One event can have multiple ultra-distance races; therefore, one event may have six races.’ I notice that as the number of events in North America has increased, so has the number of races. This phenomenon represents race directors scrambling to attract more runners to their events, not necessarily to one specific race.

For example, An event starts with only hosting a 100-mile race for the first year or two. Other distances are added in wanting and needing to grow their total participation numbers for business and permit considerations. Next thing you know, the event that started as a 100-mile race now has a 50-mile, 50-km, marathon, 10k, etc. When combining the data showing a number of events vs a number of races, we can see a sharper incline in the number of races, highlighting this phenomenon.

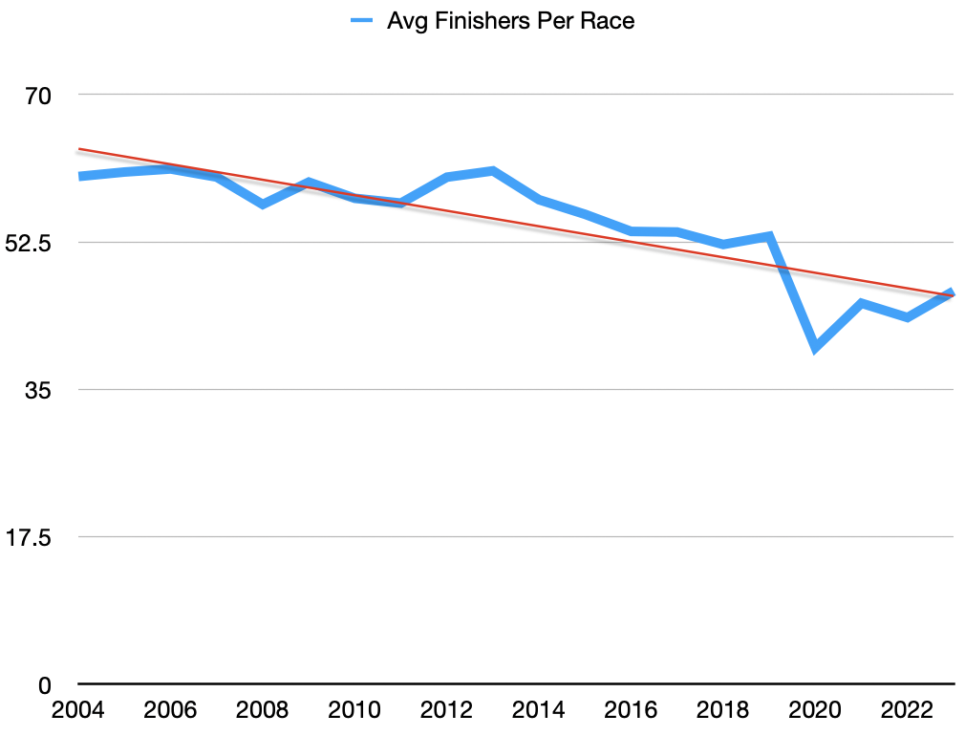

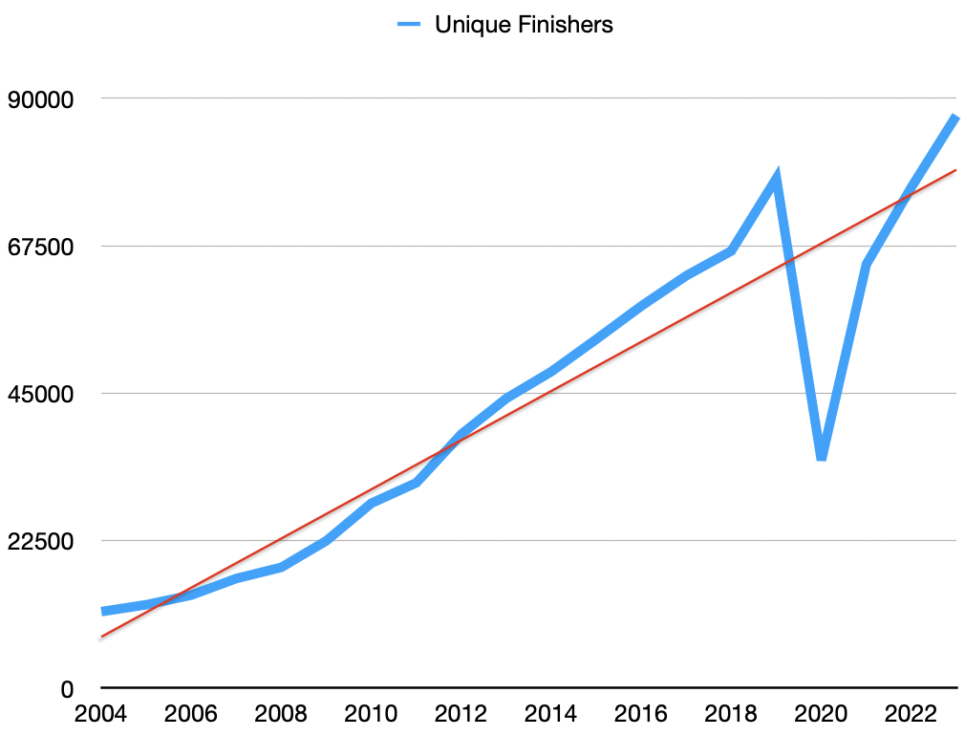

‘Unique Finishers’ refers to every individual who has finished an ultra-distance race in the year, counted just once regardless of multiple finishes. The ‘average finishers per race’ is self-explanatory; it depicts the average number of finishers per race. While the number of unique finishers has steadily increased over the last twenty years, the average number of finishers per race has steadily declined.

These considerations bring me back to my question: How many races have 40 or fewer finishers? I will use Colorado as my primary example since I only have the Colorado data present and ready.

Total Number of Colorado Ultra Races in 2013: 43

Total number of those races with 40 or fewer finishers: 20

As a percentage: 47%

Total Number of Colorado Ultra Races in 2023: 119

Total number of those races with 40 or fewer finishers: 52

As a percentage: 44%

This data shows that the number of ultra-distance races in Colorado has increased by 177% in the last decade. The number of races with 40 or fewer finishers also increased by 160%. However, the percentage of races with 40 or fewer finishers has decreased by 3%, from 47% to 44% of all ultra-distance races in Colorado.

From a supply and demand perspective, if nearly half of all ultra-distance races saw only 40 or fewer finishers, then was there a need for more events? To me, these stats show the level of irresponsibility surrounding the increase in the total number of events available. While participation in the sport is growing, these numbers show that the supply exceeds the demand. As the number of races has grown, along with participation, the number of races with 40 or fewer finishers has not necessarily decreased and has instead remained stagnant. The data should sound the alarm that more races aren’t necessarily better for the sport, and there are two reasons why:

1.) Race Cannibalization

2.) Resource Abuse

Race Cannibalization

Race cannibalization refers to a situation where multiple races are scheduled near each other in terms of time, location, or target audience, resulting in competition for participants and volunteers. This can lead to decreased registrations and volunteer availability for each race, as potential entrants and volunteers might choose only one event due to time, financial, or logistical constraints.

A decade or more ago, race organizers aimed to avoid race cannibalization by considering the schedule of all other events. Today, there is no “mutual restraint,” and race directors seemingly create events without considering the schedule of all events and how another event may create a race cannibalization scenario.

Over the years, many race directors have blamed runners’ laziness as the real reason for a lack of volunteerism. Some race directors like to theorize that runners just don’t seem as willing to volunteer as they were when volunteerism felt required for those wishing to be a part of our sport. I argue that a part of the issue is that we have abandoned the idea of ultrarunning being a community in a broader sense. Instead, we have created micro-communities within the sport, resulting in siloing. Races that have done the best job in curating a community to support their events do exceptionally well with volunteerism, while those events without a community surrounding the event suffer. Race cannibalization is the real culprit behind our volunteerism woes.

Race cannibalization can contribute to the decline in participants and volunteerism in a few ways:

- Resource Overlap: The demand for participants and volunteers increases with multiple races occurring in close proximity. This can stretch the pool of available participants and volunteers thin, as individuals may only have the capacity or interest to support one event.

- Volunteer Fatigue: Frequent events can lead to participant and volunteer fatigue, where potential participants and volunteers feel overwhelmed by the number of opportunities and thus choose to participate less overall to avoid burnout.

- Diminished Community Engagement: When too many events are concentrated in a short time frame, the sense of community and excitement surrounding each event can diminish, reducing motivation for participation and volunteering.

- Competition for Attention: Races may compete for participants’ and volunteers’ time and energy. This can result in decreased commitment from volunteers and participants as they only have so much time to give to events during a specific period.

Current and aspiring race directors can address these challenges by agreeing that we need a moment of “mutual restraint.” Now is not the time to create new events. Every time a race director builds a new event or a new race director comes in with a new event, it is the definition of insanity: doing the same thing repeatedly, expecting a different result. The more we continue to add more races and, by default, increase volunteer needs, the more we add to the tragedy of this common.

Resource Abuse

Land managers like state parks, the United States Forest Service (USFS), and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) all utilize the same ways to determine the actual amount of use the resource can handle. Federal Agencies use the National Environmental Policy Act Review Process, a “NEPA Study,” to determine how many heartbeats an area can handle before the resource is degraded or damaged.

Let me talk about this in the context of trail and ultrarunning. When a race director approaches a land manager for a permit to host an event, part of that request includes the number of runners you intend to have. On the land manager side, a NEPA study has already determined how many people each trail can handle before the resource is negatively affected. Using round numbers for our discussion,

• if the land manager has determined that a trail can handle 1000 persons in a year

• then a race director comes along to request 300 runners for their event

• If the land manager says ‘yes’ to the event request, it will take 300 persons from the 1000 “user days” available for the resource.

• This means that only 700 user days remain for all other users.

Something trail runners, and most notably trail race directors, seem to either forget or ignore is that there is more than just our user group looking to use these roads and trails for events. There are mountain bike events, adventure races, off-road triathlons, equestrian events, OHV/ATV events, fishing events, outfitters and guide services, and more. As a user group, trail runners and their directors seem only to be looking through their lens and forgetting that we must share the resource with these other groups. As we add more events to the schedule, we also take space away from these different groups. On the whole, this behavior is selfish.

If we consider the data provided above that shows the increase in the number of events and the rise in the number of unique finishers of those events, we can begin to see a trend where we are contributing to the Tragedy of the Commons by overusing our public lands, flooding the landscape with a completely unnecessary number of events. This hurts our sport. Here are some examples:

In 2022, the race director of one of the most popular 50k events in the State of Colorado decided to end their time as a race director. This was because State Park land management partners had slashed their allowable runner capacity to a number that did not match the director’s financial goals. Federal land managers also mandated that this race director implement additional risk management protocols as a condition of their permit for a different event they hosted. This would have raised race expenses to a level that made little financial sense to the RD. The race director quit directing instead of complying with land manager requests and mandates.

The race director of Colorado’s Divide 100-Mile canceled the event in 2024, citing what he referred to as a “lack of interest in new 100-milers.” He then planned a complete event redesign, looking to host a reimagined event in September with distances of 50 miles and 50km, only to be denied his permit request in what he called “a first” for him.

Several USFS ranger districts in Colorado have placed a moratorium on permitting new event requests. According to fellow race directors, these districts include the Salida, Dillon, Clear Creek, Boulder, and Gunnison Ranger Districts. We should also note here that the USFS is severely understaffed and underfunded, which has caused them to lay off much of the staff that issues and administers Special Use Authorization permits [5], meaning many of the existing races you enjoy that take place on USFS lands may not receive a permit in 2025 due to staffing and funding shortages. These race directors only report knowledge of these moratoriums because they requested permits for new events or to expand existing events, and those requests were denied.

The Trans-Rockies Run recently announced that 2025 will be their final year [6]. The event has taken place since 2007. In their announcement, they mentioned permitting as one of the issues that led to their decision. I had a moment to catch up with a few members of their staff to discuss this further. What they intimated was that there are so many races in the vicinity of their event each summer that it has become impossible for them to make the event happen logistically. Every one of those small mountain towns that the event runs through is overwhelmed by the incredible increase in post-covid tourism traffic to the point that they don’t have the additional infrastructure to support these types of events. There are so many events over consecutive weekends that finding enough portable toilets for human waste has become impossible. The permitting land managers are so understaffed and underfunded that they cannot adequately support the administration and oversight of permits. On top of rising costs, this has forced Trans-Rockies to end their historic run after 19 years.

This summer, a new 200-mile ultramarathon popped up on the Colorado scene. The USFS provided them with a permit limited to just 55 runners. Because this new race came online, the USFS chopped our permit for the Silverheels 100-Mile from 200 to 100 runners. HPRS was forced to share user days with this latest event because the new 200-miler used the same roads, trails, and trailheads as us just one week after Silverheels. We should note that one of the other reasons they were limited to just 55 runners is because a NEPA study determined it was the most users a trail they wished to utilize could handle.

In June of 2023, I wrote an article for the HPRS blog [7] about how the USFS had submitted a new cost-recovery proposal to cover the costs of Special Use Authorizations and guide and outfitter permits. Had this new proposal passed, it would have increased permit fees by 400% overnight, a reality that would have trickled down to the runners during registration. Currently, there is no indication if this rule change will occur. Based on the recent USFS layoffs, I think it is safe to say that won’t happen. Anything is possible when the new administration starts in Washington.

All of this should highlight the precarious situation we find ourselves in. The number of events that have come online in concert with the events of all other user groups has finally broken our land management partners. The land manager is forcibly implementing “mutual restraint” to protect the resource and their level of bandwidth. The USFS could still implement new cost recovery rules that would send tremendous ripple effects throughout our sport. Because race directors failed to utilize “mutual restraint” and “mutual consensus” concerning our actions, our entire sport will pay the price. We have overused and abused the resources and those whose job is to manage them.

So, What Now?

I hate to be the bearer of bad news, but some of you are about to be shocked when you learn that the race you’ve looked forward to running every year will not obtain its permit in 2025. This is a good thing for the resources and our sport, as the land managers will ultimately decide which races stay and which go since race directors have failed to see the forest through the trees. This is essentially a forcible culling of the herd. It is safe to say that those who stay will be the events who have been actively giving back to the resource through trail work efforts and fundraising. Too many race directors do not engage in trail work initiatives. They are about to discover how much that hurts them.

More races are going to go away due to race cannibalization. Stubborn race directors keep adding race distances to an event to try and attract more participants without considering that it doesn’t solve the puzzle of the lack of volunteers. It only makes it worse. Races will struggle to survive as the participant experience will ultimately suffer. None of us can deny that running in an event without enough volunteers to cater to our needs as runners makes for a less-than-stellar day. You’ll also start to see a decline in point-to-point courses and courses that feature one giant loop, as these courses require even greater volunteer needs and a larger swath of resource use.

Some race directors are going to decide to pull the plug. It’s the same work for 200 runners as for 30 runners. The finances are no longer making sense. Permits are becoming harder to acquire. Runner entitlement is on the rise. Race directors must engage in the “coming to Jesus moment, ” asking themselves if it’s worth it. In some cases, that answer will be “No.”

This is the Tragedy of the Commons. We have reached our days of reckoning and have only ourselves to blame. The warning signs were there long ago, and while some of us sounded the alarm, the vast majority ignored us as hyperbole or fear-mongering. We reap what we sow.

Resources & Citations

[1] http://trailandultrarunning.com/tragedy-of-the-trail-ultra-commons/

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tragedy_of_the_commons

[3] https://www.irunfar.com/ultrarunning-growth-in-the-u-s-through-a-geographic-lens

[4] https://ultrarunning.com/calendar/stats/ultrarunning-finishes

[6] https://sports.yahoo.com/final-race-transrockies-run-end-192600407.html

[8] Chapter 6: The One About Follow-Through. https://www.retrium.com/ultimate-guide-to-agile-retrospectives/the-one-about-follow-through