[cherry_row type=”full-width” bg_type=”none” bg_position=”center” bg_repeat=”no-repeat” bg_attachment=”scroll” bg_size=”auto” parallax_speed=”1.5″ parallax_invert=”no” min_height=”300″ speed=”1.5″ invert=”no”]

[cherry_col size_md=”12″ size_xs=”none” size_sm=”none” size_lg=”none” offset_xs=”none” offset_sm=”none” offset_md=”none” offset_lg=”none” pull_xs=”none” pull_sm=”none” pull_md=”none” pull_lg=”none” push_xs=”none” push_sm=”none” push_md=”none” push_lg=”none” collapse=”no” bg_type=”none” bg_position=”center” bg_repeat=”no-repeat” bg_attachment=”scroll” bg_size=”auto”]

(Editors Note: This article was originally posted on January 27, 2018. Since then, Gary Wang at RealEndurance.com along with Cory Smith at Ultrarunning magazine, worked together to collect and analyze similar data. Please see the bottom of this post for an update on their analysis)

This time last year I wrote a piece for the HPRS monthly newsletter where I spoke about how the “Born to Run Boom” is bust and our sport saw its first dip in participation since 1988. I utilized information provided by RealEndurance.com as the basis of my information for that artile, data that I can neither claim to be reliable or complete (though we thank Gary Wang for his hard work). I’d like to revisit this discussion with the hope that I can shed some light on the health of our sport, and what we can do to continue to support it.

In this conversation I’m going to talk about the total number of ultra finishes over the last ten years, total number of unique finishers (each ultra finisher counted just one time regardless of if they’ve finished multiple races), and the total number of events. Lastly, I’m going to discuss the injection of prize money into our sport and conclude with a brief discussion on if it’s actually helped us to further the sport or not. All of this will be discussed from a North American perspective, and will be void of discussing the health of the sport in other parts of the world.

The point I am ultimately trying to make with this piece, is that our sport is flattening out in regards to growth. The increase in the supply of races is far outweighing the demand of runner participation, and as a sport we cannot sustain growth of races at its current rates and avenues. I will argue that we need to be smarter, support each other more, and ultimately do more to celebrate the sports roots and less to try and push competition for financial reasons in order to fix this problem.

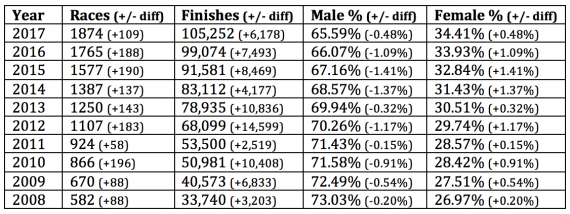

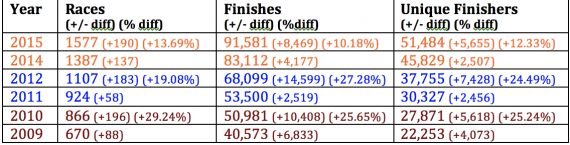

Let us first look at the total number of races and finishes over the last decade.

(Data courtesy of Cory Smith at Ultrarunning Magazine)

Discussion:

Let us talk about the finisher’s percentage between male and female ultra runners. Throughout the course of the last decade, women have consistently tightened the gap in regards to the male and female finisher percentage rate. The makeup in gender of finishers of races in our sport continues to increase with females, and decrease with males. I’ll let you draw whatever conclusion you will from that data, but I’ll add a “great job out there ladies!” as they continue to prove that they are indeed tougher than men.

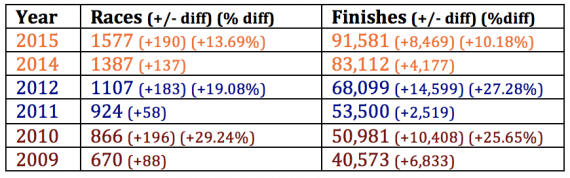

Now let us talk about total number of finishers over the last decade. This number accounts for all finishes of all runners. So if Jack Handy finished 5 ultras in 2017, his 5 finishes are counted in this number. The New York Times Best Selling book Born to Run, was released in 2009, for reference sake. The first major spike in finishers came in 2010, the year immediately following the release of the book, with a 10,408 finisher increase over 2009 (an increase of 25.65%). The second major spike came in 2012, with a finisher increase of 14,599 over 2011 (an increase of 27.28%). In my opinion, this make’s sense whereas the average person who read Born to Run probably took 2 years total to read the book and then train to finally bite the bullet and jump into ultra distance races.

This also makes sense through the total number of races over the same timeframe. Our first spike in the number of races occurred in 2010, with 196 more races than 2009 (an increase of 29.24%). Generally, I believe that the average lifespan of an ultra runner is 3-5 years. It would then make sense that the next spike in the number of races would occur 3 years later, when runners are done running in ultras and instead focusing on giving back or simply having the uber cool title of “Race Director” next to their name; this is corroborated by the second spike in races in year 2012 with 183 more than 2011 (a 19.08% increase).

After the second “spike year” of 2012, the growth in total finishers and total races started to wane off. Keeping in mind the same mentality discussed above (3-5 year ultra life space, then change from runner to race director) and we saw our next spike 3 years later (6 years total since Born to Run), this time in 2015. However, the increase between number of races and the number of total finishers does not follow the same trends of 2010 and 2012.

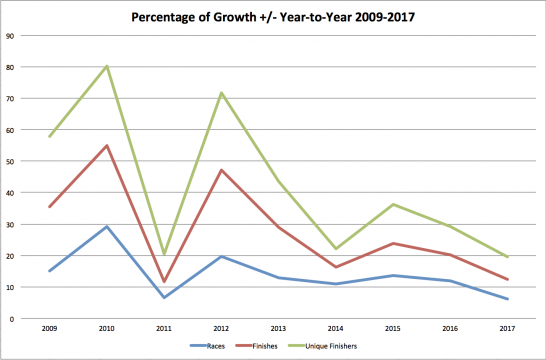

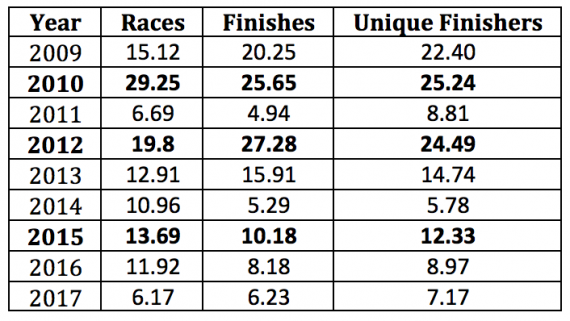

Between the three major spike years, we saw the increase in the number of races decline by -10.16% (2010/2012), then -5.39% (2012/2015) respectively. The spike in the number of total finishes in 2012 was higher than the increase in 2010 by +1.63%, but the increase in finishes in the 2015 spike year didn’t fare as well. The increase saw a -17.09% difference over the spike of 2012. That’s HUGE. What the hell am I talking about? Let’s look at the number of unique finishers over the same time in order to look deeper. But first, here is a visual representation of what I’m talking about.

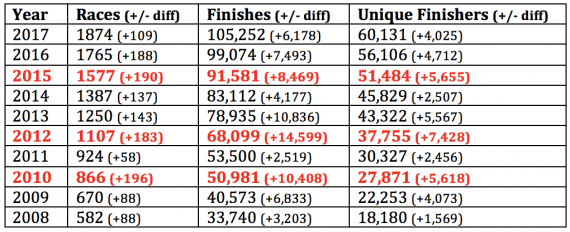

The total number of races, finishes, and unique finishers over the last decade.

(Data courtesy of Cory Smith at Ultrarunning Magazine)

A “unique finisher” counts each ultra finisher just one time. I have highlighted the three major spike years for reference.

And let’s plug the unique finishers number into the growth percentage for “spike years” table as well.

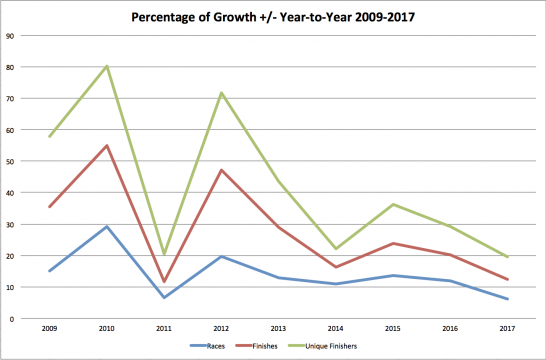

So here is what I’m talking about. Yes, our sport continues to grow and we saw another spike in 2015; however, the 2015 spike was not at all like the spikes of 2010 and 2012. Year after year, with the data provided, we can see that the number of races, number of finishes, and the number of unique finishers has increased for the last decade. What is alarming, in my opinion, is that the last spike year, 2015, saw a huge deficit in the percentage of growth as compared to years 2010 and 2012. Visually you can see that the spike is much smaller (below).

To clarify, the spike in races in 2010 was clearly a result of the demand of racers brought on by Born to Run. The spike in 2012, was a smaller spike in races but a large spike in finishers and runners. The spike in runners was not met by the spike of new races because there clearly enough races to handle the runner load. The spike of races in 2015 was very comparable to the spike of races in 2012, so we should have seen the same spike in runners that we saw in 2012… however we didn’t. This is saying that our race market is saturated above the needs of runners.

Here is the percentage of growth from year to year in each category.

Given the visual above, we can safely say that either we need more runners to come into the sport while the growth in the number of races stays the same, or this will cause more races to disappear. The profit margins between number of unique finishers, total finishes and races should be as spread out as they were in spike years 2010 and 2012, instead we’re seeing a flattening out of the market and the percentage of growth trends have been on the decline since 2010, but more drastically since 2012.

In 2010 runners drove the market. In 2012, the runners drove it again. What’s currently happening is an increase in races hoping to attract a surplus of runners, however on our spike years we know that runners drove the market, not the races. So we need to attract more runners, not supply more races… theoretically. We need races to do more to attract people to ultra again, and if we can do that.. it will support the need for more races to come around. The magic number seems to be 25%, we need 25% more runners this year to support the large spike in races coming online.

So, how do we draw in more runners?

I’ve heard many times over the last decade or so, that the way for our sport to grow is to offer prize money. Some of the races that ascribe to this notion are The North Face Challenge, Ultra Race of Champions, Speedgoat, and Run Rabbit Run. Because Run Rabbit Run offers the largest of the purses, I’ve chosen to use them as a case study for this mentality.

In 2011, Run Rabbit Run announced the creation of a new 100-mile race to coincide with their 50-mile ultra in Steamboat Springs, CO. They were the first race to suggest that the solution to the problem, “How do we promote and grow our sport?” was injecting prize monies into races. From an article written on iRunFar.com when the story first broke, they stated (http://www.irunfar.com/2011/12/the-answer-to-the-100k-question-the-run-rabbit-run-100-mile.html):

“Those who have run the Run, Rabbit, Run 50 or who have read the race reports about it, know that it is one the most beautiful, best run, and most fun ultramarathons in the country and it’s put on by and for runners. The 50 is an old school ultra, where the goal is to put on a first-class, well-organized race and give money in excess of expenses to local charities. The race’s popularity led to a long waitlist for the 50 miler this year.

…

The objective of the new Run, Rabbit, Run 100 is to attract the best field of ultrarunners in the world to Steamboat Springs. How? By offering real prize money.

…

The ultrarunning world is constantly evolving. (What isn’t?) In the context of the sport’s current state and its recent growth trajectory, it appears to be akin to road racing three decades ago and triathlons a bit more recently. Runners and races are going to make money. There’s nothing wrong with that… so long as two things don’t significantly change.

First, for the spirit of the sport to continue without radical alteration, the sport’s top runners must continue to race for the love of running and competition with prize purses being a way to support their running lives. If you’d seen the top dogs throw down at the TNF 50 last weekend, this very much remains the case.

Second, organizers must continue to put on races that cater to the main body of the sport while meeting or exceeding those runners’ expectations. That’s not all, those race organizations must continue to be based on passion for that is the source of the je ne sais quoi that you see at Hardrock and Wasatch and Massanutten and Stone Cat and Speedgoat and Chuckanut and all of the many other events that stir emotion in those who’ve experienced such a race, be it as racer, crew, volunteer, or spectator.”

Having run the Run Rabbit Run 50-miler prior to the creation of the 100, I agree whole heartedly that the race was indeed “old school” and “one of the most beautiful, best run, and most fun ultramarathons in the country, put on by and for runners.” That was never in doubt and I can agree with that summation on all counts.

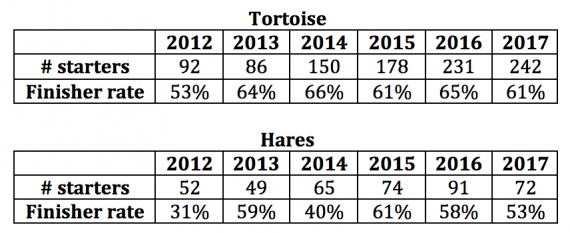

So did prize money really attract the best field of ultrarunners in the world to Steamboat Springs? If you go onto Ultrasignup.com and browse through the results of the Run Rabbit Run 100 for years 2012-2017, I think you’d be hard pressed to make the argument that they have. Certainly, some of the best from Colorado have shown up, but I don’t think you could say that in any given year that the race with the highest prize purse in North America has hosted the premier elites of the world. Furthermore, it has been the tortoises that have outshined the hares division at that race, by consistently having a higher finisher percentage rate. That’s right, those who are driven by the idea of winning a huge prize purse have performed worse than those who are not driven by money.

As to the points made by Run Rabbit Run in the article:

1.) “for the spirit of the sport to continue without radical alteration, the sport’s top runners must continue to race for the love of running and competition with prize purses being a way to support their running lives.”

I disagreed then and I still disagree now. For the spirit of the sport to continue without radical alteration, we need to focus on their second point (below) and forget the first. EVERYONE needs to continue to race for the love of running, PERIOD. It is NOT the competition, prize purses, or the elites being able to support their running lives through these avenues that made our sport what it is, nor is it the reason we saw spikes in attendance in 2010 or 2012. Where in the books Ultramarathon Man or Born to Run, did we read about huge prize purses, competition, or elites? Instead we read books about the everyman, and woman, and their abilities to overcome adversity through emotion filled athletic endeavors. Which directs us to their second point..

2.) “Second, organizers must continue to put on races that cater to the main body of the sport while meeting or exceeding those runners’ expectations. That’s not all, those race organizations must continue to be based on passion for that is the source of the je ne sais quoi that you see at Hardrock and Wasatch and Massanutten and Stone Cat and Speedgoat and Chuckanut and all of the many other events that stir emotion in those who’ve experienced such a race, be it as racer, crew, volunteer, or spectator.”

They hit the nail on the head here. I don’t believe for a second that the prize money has been what draws runners to Steamboat for Run Rabbit Run. What draws them is the old school ultra, during a gorgeous time of year, by runners for runners. What draws them there is the opportunity for the mid and back of the pack runners to share some miles, even if just a few, with the elites. Those who are the most successful at this race continue to be those who run for reasons other than prize money.

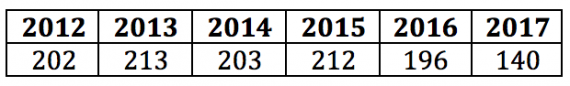

Let’s look at the total number of starters in that old school, fun, gorgeous, well run 50-miler they’ve hosted in Steamboat since 2012.

Q: Did the injection of prize money and a new 100-miler increase participation in the Run Rabbit Run 50 in Steamboat?

A: No.

Q: Has the number of folks starting the event trended upwards since the creation of the 100-miler and the injection of prize money?

A: No.. it has trended down.

They had an awesome old school 50-mile event, with a long waiting list, that they seem to have ruined by instead focusing on a new 100-miler with a huge prize purse, or New School.

So then, let’s look at the number of starters for their 100-miler, and it’s two divisions, over the same time.

The number of runners in their tortoise division has seen increased growth, year-after-year, while the finishers rate has remained high, over 60% since 2013. Meanwhile, the growth of the Hares division has been stagnant, with the finishers rate remaining below those of the tortoise division. This speaks volumes to me. Run Rabbit Run hasn’t grown because of the prize money, and in fact the addition of the 100-miler has hurt the 50-miler. That was the idea though, 50-milers don’t make a race director money, while 100-milers do. That’s just a fact regardless of if it’s Run Rabbit Run or any other race or series with multiple distances. No one is flocking to Run Rabbit for the prize money, they’re flocking there for the experience.

I encourage you to look into the other races that offer prize money, to see if they’ve trended any differently than Run Rabbit Run and their prize purse “experiment.” Meanwhile, Run Rabbit Run proved a serious point, the point being the answer to our problem. How is our sport going to grow over time? How are we going to attract more runners?

The answer isn’t in prize money, it’s in the “je ne sais quoi” as they put it. It’s not by worshiping the elite and giving them the opportunity to win thousands of dollars in order to support their desire to be full time elite runners. It’s by celebrating all runners, each and every single one that comes into the sport, the same. That’s the je ne sais quoi I myself have experienced at races like Stone Cat and Massanutten, and all of the other races that have stirred emotion in myself, and others. It’s by providing an amazing experience for every runner at every race.

As race directors, we’re going to bring new runners into our sport at the level of growth we need, by being our genuine and authentic selves. Being human to other humans. By celebrating each and every runner as equals and as a vital piece to the greater puzzle of ultra. We’re going to get there by humanizing the sport without dehumanizing those who participate here. By treating women the same as we treat men because they deserve it, and by the numbers they’ve proven that they’ve earned our respect. We’re going to bring new runners in by leaving the lights on for every runner, by making sure each aid station is fully stocked for each runner and open until all are accounted for, and by sinking our money into hosting truly world-class events every single time. We’re going to get there by working together to be fair, transparent, and holding each other to a higher standard.

We can and must do better together. We must take greed out of the equation. We must stop creating new races, and injecting prize money, simply because we think it means more money into our RD pockets, though the numbers show that the money isn’t going to follow. We must do more to encourage folks to join us, to be a better version themselves, to recognize their human potential through unique athletic accomplishments.

UPDATE: On February 6th Gary Wang of RealEndurance.com issued the following on Facebook. His data corroborates what Sherpa has stated above.

[/cherry_col]

[/cherry_row]