By HPRS Staff Columnist Holly Rapp

I’ve been working on a piece on inclusivity and diversity in our running community for quite some time. But the devastating news of runner Ahmaud Arbery’s murder has taken precedence over everything I wanted to write and all I thought I should, or could, say.

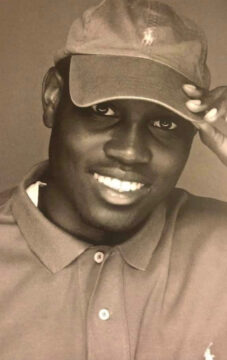

Though the case has been publicized only recently, Mr. Arbery was killed back in February; this delay in coverage is one telling component of the story. A black man, Mr. Arbery loved to run in Brunswick, the small, suburban Georgia town where he lived. Many in the community report they knew Mr. Arbery was a runner and that he was a common sight passing through the Satilla Shores neighborhood.

On a beautiful Sunday in February, Mr. Arbery set out for a run just as many of us did that day. Maybe it was a long run, or maybe just a quick outing to enjoy the lovely afternoon.

But Mr. Arbery’s run diverged starkly from ours shortly after it began.

As Mr. Arbery passed the front yard of a white man, Gregory McMichael, Mr. McMichael yelled for his son, Travis McMichael (also white), and together they retrieved their guns: a shotgun and a .357 magnum revolver. The two then ran to their truck and started to pursue Mr. Arbery as her ran. When they caught up to him, after a short struggle, Mr. Arbery was killed by at least two gun shots.

—

The McMichaels claim Mr. Arbery fit the profile of a suspect who committed several robberies in the area. Before this fatal incident, two Satilla Shores residents had already called 911 to report a black man running in the area. These calls raise important questions about who has the right to run in the eyes of some and why we runners are viewed so differently despite participating in the same shared sport.

Both the local community and legal authorities in Brunswick dispute highly the exact details of the case, which has ignited fierce debate over racial profiling, self-defense laws, and Georgia’s citizen’s arrest statues. All involved are divided sharply in their opinions of what took place and whether the McMichael’s had the right to kill Mr. Arbery. While some try to justify it, others say it is a hate crime and a modern-day lynching.

But what is clear to me, no matter the precise specifics of the incident, is that a black man is dead, killed by two white men, who pursued him in a truck as he was out for a Sunday run.

—

Mr. Arbery’s case was largely kept quiet outside Brunswick until recently when major news outlets like The New York Times and The Guardian began to report his story. Coronoavirus has only complicated things further as those in the community who want to support Mr. Arbery are unable to gather and protest in order to publicize and draw attention to his death.

It remains to be seen what will happen from here with Mr. Arbery’s case.

For now, we, the members of the running community, are one of many groups left to ask what we have to do with this incident.

The easiest response would be to say it falls outside our purvey, that the problem came from outside the running community and therefore there is nothing for us to do.

But that view, I would argue, is far from correct.

I think we the running community have a responsibility to recognize this incident, to acknowledge it happened, and to learn we can about, and maybe from, it. I’m calling for us to talk about what took place, to try to understand how such a thing happened to a fellow runner, and to formulate a response to this horrific killing.

One seemingly easy reaction may be to say we need to talk more about safety for all runners, and that may well be a valid point. But I put absolutely no onus for this incident on the victim or his actions while running that day. I believe, furthermore, that we should be able to run freely without worrying about being chased in a vehicle and shot, a statement so absurd I can’t believe I’ve had to articulate it. It feels like such an outlier that our normal safety conversations don’t even cover such a thing. It has, however, sadly happened, so perhaps it’s something we do need to address? I really don’t know.

Approaching the issue from a different direction, I would urge us talk about it means to be part of our running community. What kind of community we want to create? As participants, what do we want our group to look like? What public face do we want to present?

I personally advocate for us to be open and purposefully inclusive, a community that welcomes all runners, no questions asked, including black people like Mr. Arbery. Race, gender, class-status, religion, creed – our community, in my opinion, should accept and support everyone, regardless of these factors and any others. I believe this intentional inclusivity and celebrated diversity could act as a powerful foundation for our community, one we could model in the hopes that others may someday join us.

—

As a nonwhite runner who grew up as the only nonwhite person in a small, conservative midwestern town, perhaps these issues hold special significance to me; perhaps Mr. Arbery’s story hits closer to home than most.

Though I suffered nothing like Mr. Arbery, I remember vividly other kids driving their trucks onto the sidewalk to scare me as I ran. They threw rocks and cans at my head from their trucks and taunted me with slurs like “chink.” Virulent racism and discrimination defined my childhood and appeared in every aspect of my life, including running.

Racism is real for many runners. It’s an issue we’ve long ignored or treated as unimportant, but it’s time to change.

—

Now we face a important task: we must decide what stance we will take in the face of this killing. How we will present ourselves to the public in response to what has happened? How will we respond to fellow runners who continue to experience such prejudice and unjust treatment? What can we do to support those members of our community?

Is our community going to acknowledge and address Mr. Arbery’s death publically in any meaningful way? Has Mr. Arbery’s death received the same response as those of white runners in the past? If not, what does that disparity mean? What does our treatment of this case say about our community; what message do we want it to convey about us? And how do we move forward together after this killing?

I certainly don’t have the answers to everything; it feels, as you can see above, like all I can think of are questions. At this point, then, I might suggest humbly that each of us runners think seriously about these questions, formulate our own inquiries, and to consider carefully what we do from here.

And in all our discussions, let us never forget that at the core of everything is the life and death of a person, a fellow runner, Mr. Arbery.